Business-Driven Architectural Capabilities

Generally, when I am hiring for any technical position, I am less interested in what a candidate knows and more interested in how they think. This is doubly true when evaluating prospective architects. To this end, I’ll often directly ask “What is the best architecture?” A surprising amount the time, I get answers like “microservices.” In my experience, this type of answer often betrays a lack of architectural thinking. I won’t typically terminate the interview right then and there. I want to give them the benefit of the doubt as it is easy to misunderstand a question and it can be challenging to determine expected answers in the heat of an interview (especially arguably trick questions like this). I will always ask some follow-up questions as an opportunity to course-correct, but historically they haven’t and thus I have yet to hire someone after an answer like that.

Architecture doesn’t exist in a vacuum and we must avoid projecting our own biases and preferences into this type of work. We can’t have the architecture conversations without first having business conversations. Anything less is putting the cart before the horse, which is a formal architecture anti-pattern. In this post, we look at where architecture decisions come from, how to avoid common anti-patterns, and look at a process to begin to infer architectural capabilities from requirements and conversations with business stakeholders.

This post is part of a series on Tailor-Made Software Architecture, a set of concepts, tools, models, and practices to improve fit and reduce uncertainty in the field of software architecture. Concepts are introduced sequentially and build upon one another. Think of this series as a serially published leanpub architecture book. If you find these ideas useful and want to dive deeper, join me for Next Level Software Architecture Training in Santa Clara, CA March 4-6th for an immersive, live, interactive, hands-on three-day software architecture masterclass.

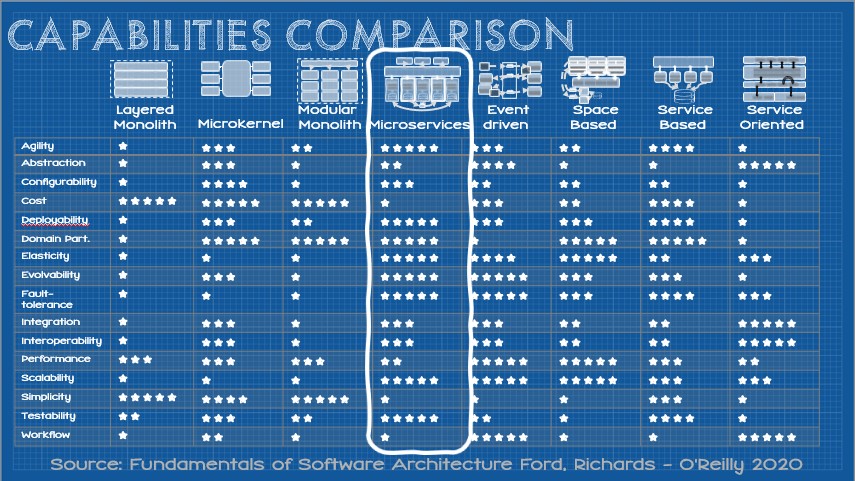

One common source of this type of thinking can be traced by looking at the respective capabilities of various architecture component patterns. I spent a great deal of time with Neal Ford and Mark Richards on the No Fluff Just Stuff conference tour. Over the past decade or so I watched their relative scoring of patterns evolve. The end result can be found in their presentations and their 2020 book, “Fundamentals of Software Architecture”. Eventually the model evolved to a star-rating system, with 1 star being the “worst” and 5 stars being the “best”. The result of their work can be seen in the following image:

When looking at this score table, it’s easy to proclaim microservices a clear winner - after all it has the most 5-star ratings of any of the patterns. Assuming the highest-scoring option is therefore the best is another antipattern known as the “Out of Context Trap.” If you’ve ever used some god-awful piece of enterprise software, you’ve experienced this. Regrettably the customers of such software are rarely the users. Committees tasked with selecting and standardizing on a piece of software will often make a decision based on a feature matrix and whichever has the most check marks will often win out. Users of the software will often make a decision based on the context of the problems they are trying to solve but committees often lack this context. Capabilities don’t always equate to success - they have to be the right capabilities.

“The Out of Context Trap: Blindly selecting the highest scoring, or most feature-dense option without the context of the problems that should be solved.

Let’s look at a concrete and tangible example. In the mid-to-late 1970s, the VHS cassette and VCR were introduced to the consumer market. VHS remained a dominant media format until the late 1990s, when DVD replaced VHS as the dominant format - and for good reason. DVDs offered a higher-quality viewing experience and had many capabilities that VHS didn’t have. Among those capabilities are the capacity for random access and the ability to jump to particular chapters, special features, multiple audio tracks, multiple languages, digital audio, interactive menus, commentary, etc. But I digress…

It has long surprised me that the VHS was so successful given a far superior, alternative media that was available at the same time. I think you know what I’m talking about - let’s say it together on three: 1…2…3… LaserDisc (wait, did you think I was going to say Betamax?)

Also released in the mid-to-late 1970s was Laserdisc, an optical media that was objectively superior to VHS. Let’s look at a feature matrix comparing VHS and laserdisc:

| Capability | VHS | Laserdisc |

|---|---|---|

| Quality | Low | Medium |

| Random Access | No | Yes |

| Chapters | No | Yes |

| Special Features | No | Yes |

| Additional Audio Tracks | No | Yes |

| Digital Audio | No | Yes |

| Interactive Menus | No | Yes |

| Media Retail Cost in 1979 | $80-100 | $30-40 |

| Player Cost in 1979 | $999 | $650 |

Do you see a clear winner here? By virtually every metric, the laserdisc was superior. It was better, cheaper, and more capable. So why, in the late 70s and early 80s was only one Laserdisc player sold for every 50 VCRs?

Laserdisc solved the wrong problem.

You have to consider the context at the time. Building a library of home video wasn’t yet in the consumer collective consciousness. At that time, the way we consumed video content was via broadcast television. This meant that, to watch any given program, you had to be at home and tuned to the correct channel when the content was broadcast. If you were away, or someone was already watching something else on a different channel… you missed out, and that was it. Maybe you would get another chance when the program entered syndication in a year, but you would still need to be in the exact right place at the right time to view the rebroadcast. The market had spoken we were primarily interested in time shifting - the ability to record one channel at a given time for later viewing while we were away, or while a different channel was being watched live. Although the cassettes were relatively expensive, they were highly reusable. Once we had watched the program we didn’t want to miss, we were free to record over that content with a new program. It’s right there in the name, Video Cassette Recorder. The idea of building a library of video didn’t come until later, and by that time we had a large install base of VCRs in the world. Despite its technical advantages, Laserdisc never stood a chance.

Architecture Must Solve the “Right” Problem

Undoubtedly microservices are cool (and look good on a resume). A highly evolved and advanced architecture is certainly something that can confer bragging rights, but if that architecture doesn’t translate to real, tangible business value it’s moot. This is why architecture decisions must be made, at least largely in part, based on the business problems that need to be solved.

In our last post we talked about architecture capabilities, but these must be inferred and derived from what the business needs (which is, I should add, often distinct from what they say they want.) A common pitfall I have seen in my career is architects “waiting” for the business to give them the non-functional requirements of the system. Remember these capabilities form the part of the language of the architect and not the language of the business. In any event, if you wait, you’ll be waiting a long time.

Moreover, if they did somehow communicate needs in the language of architecture, remember this is not their native tongue and what they say and what they mean will rarely line up. A common example of this is, perhaps the business has expressed interest in adopting microservices. My interpretation of this is that they want some capability or capabilities that pattern promises. As you’ll see in this series, there are many paths to those capabilities with radically different trade-offs. It is the responsibility of the architect to translate the language of the business and tease out which capabilities that are needed–the “why” is more important than the “how.”

Beginning the “Business Conversation” Preparing for the First Meeting

The process I often like to start with begins with exploring the business domain of the customers/users of the system. What are their typical problems, pain points, and challenges they face on a daily basis. From there I begin reading documents and decks detailing requirements, vision, as well as available marketing materials. Keep in mind these can be vague and laden with buzzwords. You may need to search for them, but they almost always exist. In order for any project to be greenlit, the business first had to outline a clear vision and make a compelling case to investors, leadership, or budget committees. Notably, this will be true whether you are in a greenfield or a brownfield. Arguably this is even easier in a brownfield because there will also exist well-known challenges, KPIs to improve, and OKRs that can be measured.

Try to read each line in from the perspective of the target customer. Try to determine how the ideas being described brings new value to the user. Ultimately, what you’re doing at this point is creating a mental draft of a vision and understanding of the project. Your first draft is exactly that, a first draft. There will be knowledge gaps, misunderstandings, and implicit assumptions that will need to be corrected. After consuming the available material, open a document and try to articulate your understanding of the project and its goals. Write down questions, enumerate assumptions, and identify areas for further exploration.

Next I aim to validate and align my vision to that of the business. Identify key stakeholders on the project. Look at the authors of the documents you’ve read, and don’t be afraid to ask them who else should be part of a conversation around the core goals of the project. Set up that first meeting.

Identifying Stakeholders

Architecture is more than system design, often architects must also lead both technical and organizational change. As my friend Daniel points out, there are five components necessary to effect change in an organization. They are:

- Authority

- Accountability

- Responsibility

- Know-how

- Will

I have yet to meet an architect in the wild who possess all five. I should point out that know-how may be lacking at this stage - that is ok, it is not a failing. If the problem is well-understood it will often illuminate the path to know-how (the important part is starting from the context of the problem to solve). That said, generally architects will have know-how, will, and either accountability or responsibility. It is imperative to take stock at this stage, what do you have, and who has what you lack. For every element missing, you will may find an individual, team, or committee who controls that element. These form the foundation for your list of key stakeholders because, if you don’t have consensus, alignment, and buy-in from them; the effort is likely doomed to fail.

Additional stakeholders may be individuals driving the project vision. Identify these people, along with who is communicating the vision either up or down the organization (e.g. the authors of the documents we discussed above).

Building Trust and Alignment - The First Meeting

In that first meeting my goal is alignment. To kick this off, I always explain my goals and the role of architecture. It typically begins something like this:

“My name is Michael and I’m an architect on this project. We’ve got a clear backlog of features to deliver, and my job is to think about the best way to deliver these features. There is a near-infinite number of ways to write software to deliver features and I want to ensure that we choose the optimum path for the present and future of this project. Before we get too far, I want to validate that our vision and understanding is aligned.”

I’ll continue by detailing my business-level understanding of the project and its aims, pausing to listen at every opportunity. Again, my first draft is almost always incomplete and this conversation is an opportunity to flesh it out. Next I go through my questions followed by validating my assumptions. I try to pay particular attention to things like budget, timeline, and hiring plans. I want to know are we building an MVP or a POC. What to we hope to achieve with the first release (of either the new or “modernized” system).

Assuming we are aligned on understanding and vision, I next want to understand each stakeholders friction and pain points. What “keeps them up at night?” This can be part of this initial meeting or take place in subsequent conversations. These conversations strengthen my understanding, builds trust and empathy, and enables me to better communicate decisions and proposals to these individuals in meaningful context. These conversations arm me with the tools necessary to communicate more persuasively and contextually to stakeholders. During these initial conversations, resist the urge to jump into solutioning, this is not yet time time. If potential solutions jump to mind, I capture them in my notes in the moment. These potential solutions are typically driven by a combination of what I am hearing and implicit assumptions I’m bringing in. I use these ideas an an opportunity to enumerate and validate my assumptions, but I strive to ask questions centered around the problems being discussed, not the solution I am imagining.

I usually close by asking how the stakeholders imagine this system will look like in five and ten years time (will it be largely static, or radically different?) I list the reading I have done to date and ask if there is anything else I should review. Depending on the scope of the project, this first meeting can take quite some time so be sure to allow enough time for this conversation. I always take copious notes as there is still much work to do.

At this point, I go back through my notes and any other documents line by line and try to tease out architectural capabilities. My goal is to produce a braindump of candidate capabilities where each one can be directly tied back to pain points or some statement the business made (either in that last meeting or in existing documents). Linking the architectural capabilities back to challenges, requirements, and vision is of the utmost importance. When you have your next meeting, you need to frame every decision in a context that they understand. Also, begin to think about things that are often not said in marketing and vision documents (e.g. scalability, availability, security, fault-tolerance, etc.).

By now you may have a dozen or more architecture capabilities. We want to whittle this down and begin to prioritize.

Qualifying and Quantifying Capabilities - The Second Meeting

Bring together the key stakeholders again. Start by restating your understanding of the vision and remember to speak in their terms, not yours. If you are aligned, begin to work through your list of candidate architectural capabilities framed in context, described in terms they understand. When speaking about Availability, for example, don’t ask “How important is high availability” I promise you will almost never get a useful answer. Instead, ask questions like “How negatively would the business be impacted if we experienced 6 seconds of downtime per week? How about 60 seconds?” and so on, until you have a target SLA.

Here is an availability table for reference:

| Availability level (uptime) | per year | per quarter | per month | per week | per day | per hour |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 90% | 36.5 days | 9 days | 3 days | 16.8 hours | 2.4 hours | 6 minutes |

| 95% | 18.25 days | 4.5 days | 1.5 days | 8.4 hours | 1.2 hours | 3 minutes |

| 99% | 3.65 days | 21.6 hours | 7.2 hours | 1.68 hours | 14.4 minutes | 36 seconds |

| 99.5% | 1.83 days | 10.8 hours | 3.6 hours | 50.4 minutes | 7.20 minutes | 18 seconds |

| 99.9% | 8.76 hours | 2.16 hours | 43.2 minutes | 10.1 minutes | 1.44 minutes | 3.6 seconds |

| 99.95% | 4.38 hours | 1.08 hours | 21.6 minutes | 5.04 minutes | 43.2 seconds | 1.8 seconds |

| 99.99% | 52.6 minutes | 12.96 minutes | 4.32 minutes | 60.5 seconds | 8.64 seconds | 0.36 seconds |

| 99.999% | 5.26 minutes | 1.30 minutes | 25.9 seconds | 6.05 seconds | 0.87 seconds | 0.04 seconds |

This line of question allows me to qualify and quantify availability to a percentage of uptime. In my notes I will record who answered these questions so when I document our architecture decisions, I have solid sources citations so when I communicate these to the rest of the organization, it’s clear I didn’t just pull these numbers and decisions out of a hat.

Around fault-tolerance, I ask questions like “Are there areas of the system that are operationally more important than others?”

Around security, I ask “What would the impact of a data breech be to this project and organization? What are the most important assets?” This helps me determine if security should be an express capability, or an implied capability (in other words, is a baseline of security and best practices enough or are there particularly sensitive data assets that must be secured beyond best practices.)

Around scalability, I ask how many users we expect the system to support in a year, five years, and ten years.

For each capability on my list, I also want to find out what is on my list that doesn’t actually have to be there. Some are business-critical, some are important, some are nice-to-have, others we could take-or-leave, the rest we can eliminate.

Our working artifact here is a list of capabilities that we must prioritize. Don’t aim to get stakeholders to prioritize the entire list, you’ll likely go in endless circles as different stakeholders will disagree on some of the minutia. Build consensus on what is business-critical. In a vacuum, capabilities like security, scalability, or availability might seem mission-critical, but by framing your questions in the way described above a much clearer picture will emerge.

This second meeting is an opportunity to further build trust, foster a long-term cooperative relationship, and ultimately leave with no more than 4 ranked/prioritized business-critical architectural capabilities. You must lead this meeting because even if you have determined the business is comfortable with three nines (99.9% uptime), the stakeholders might still put this at the top of the list. In these cases I explain that “if we make this a business-critical capability, I’ll make very different decisions that will dramatically increase cost, development time, and project risk. We agreed we can handle 10 minutes of downtime per week so I’m not sure the value of overengineering for higher uptime makes economic sense.”

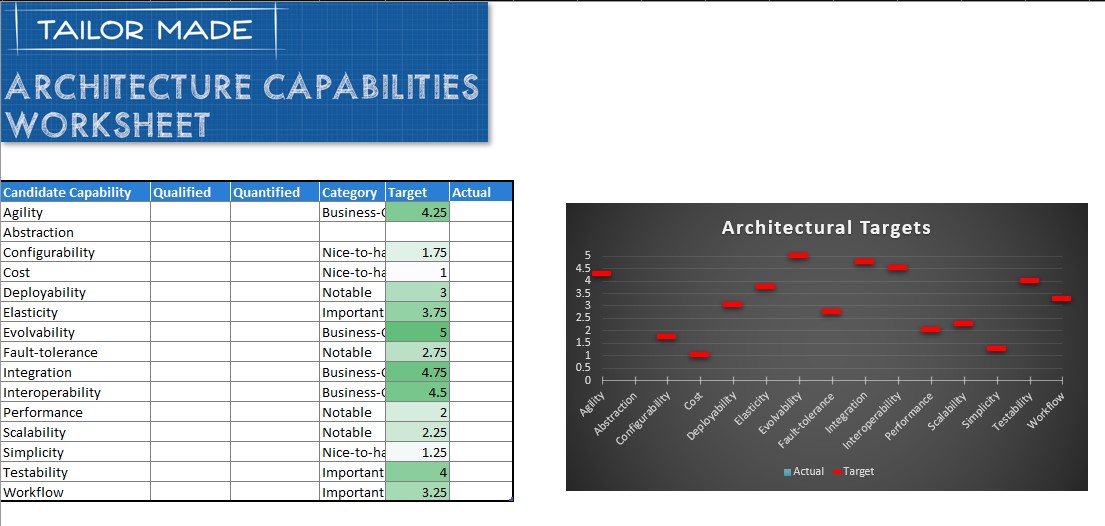

What do these rankings ultimately look like? The Tailor-Made model dictates that the importance of capabilities are quantified on a scale of 1-5 broken at ever quarter-of-a-point. (e.g. the number one business-critical capability has a score of 5, the next 4.75, the next 4.5, and the fourth if applicable will score 4.25)

| TM Priority Score | Importance |

|---|---|

| n > 4 | Business-Critical |

| 3 < n >= 4 | Important |

| 2 < n >= 3 | Notable |

| 1 < n >= 2 | Nice-To-Have |

At the conclusion of this meeting, we have ranked business-critical capabilities, each qualified, quantified, and linked to documents and/or past architecture meetings. Following the meeting, I begin formally documenting these characteristics and their score. This is in the form of an architectural style document that first outlines a summary of the vision and then identifies the business-critical characteristics. Wherever I can, I aim to quote and link my sources. I also open a copy of the Tailor-Made workbook where I begin to capture these ranking as capability targets. The templates for these will be introduced later in the series.

Continuing to Evaluate and Eliminate Candidate Capabilities

By now architecture and business are (hopefully) in close alignment. You should possess a good shared vision and a reasonable understanding of the problem space, the needs of the customer, and the goals of the project. At this point, I will take a stab at prioritizing and scoring the remaining capabilities. When completing this exercise, be mindful of the answers you received about the business’ vision and expectations for the future. Architecture is not just about V1.0 or V10.0 (and, of course, we must have a V1.0 before we can have a V10.0). The rankings you produce are not set in stone. This is just another tool to strengthen your understanding and evaluate what you have with an eye toward the future.

My workbook begins to look like this:

In subsequent conversations, I will verify my rankings of Important, Notable, and Nice-to-Have capabilities. I usually introduce these in pairs rather than present the entire list to the business. The entire list can be potentially overwhelming (and lead to relitigating previous agreements). I’m only trying to gauge relative importance below business-critical.

The Tailor-Made Architecture Model

The Tailor-Made Architecture Model allows very fine-grained control of architectural capabilities, so having this wider set of targets is a very valuable starting point for the rest of the process. It is often possible to get very close to exactly hitting each of those targets. It’s simple, but it’s not easy.

Wrapping Up: Business-Driven Architecture

In our journey through architectural design, it becomes evident that architecture isn’t just about building robust systems—it’s about aligning those systems with the business’s core objectives. Too often, the allure of technical perfection can overshadow the real-world problems we aim to solve. As we’ve seen with the tales of VHS vs. Laserdisc and the pitfalls of the “Out of Context Trap,” success doesn’t always go to the technically superior. It goes to the solution that best addresses the market’s immediate needs.

The Tailor-Made Architecture Model serves as a testament to this philosophy. It underscores the necessity of prioritizing architectural capabilities based on genuine business requirements and producing measurable business value. Whether you’re an architect seeking alignment with the business or a stakeholder aiming to understand the intricacies of system design, remember: architecture is as much about understanding the problem as it is about devising the solution - “Why is more important that how.” Let’s never architect in a vacuum. Instead, let us ensure that every architectural decision made serves the larger goal of the business, now and in the future.

There is much more to come!