Hurdles of Innovation

If you’re reading this there is a better than average chance that you either are an innovator or will be soon. People who regularly attend conferences, read widely, and follow obscure and longwinded blogs tend to skew venturesome; active information-seekers with diverse social groups and information sources, possess breadth of knowledge, are more willing to explore and adopt new ideas, and are able to cope with higher levels of uncertainty. If you are an innovator then, according to current research, you are part of a vanishingly small demographic that makes up just 2.5% of the total population. The unique cognitive and social diversity of this group offers perspective and insight into ideas, opportunities, possibilities, and solutions ahead of the mainstream.

Perhaps you see the solution to a problem right now. Congratulations, you have an idea–an innovation–that just might make a material difference in the lives of a lot of people. How do you get the other 97.5% of the population to adopt your solution? Will your innovation take off by itself on the merits of its benefits? Unlikely. If the best ideas always won, I wouldn’t be writing this. Even when the idea or innovation has clear and obvious advantages, skeptics must be won over. Old, entrenched habits must be abandoned. Innovations must be evaluated, explored and increasingly accepted until they reach critical mass (only then will they take off). This process can take years or may never succeed at all. Your efficacy as an innovator depends on your ability to optimize and streamline this process, influence your peers, and ultimately effect change in the real world. There is an art–and a science–to the diffusion of innovations.

This feels like a vainglorious boast to actually write but, for as long as I can remember, I have had a mind for solutions. Given most sets of problems, I have long been able to quickly “see” a solution. I suspect it has something to do with my other, multi-decade, career because, in that world, you look at problems and impossibility very differently. This ability has driven my tech career quite far and led me to modest success in the software architecture space but, if I look back at my 25+ year tenure in tech, I see that–good ideas or not, solutions or not–I was rarely effective. It turns out that I spent many years overvaluing my technical skills and blaming others in lieu of a meaningful postmortem. However “smart” I thought I was, I still had a lot to learn.

Our technical skills are just the ante. They get us into the game but all they do is get us into the game. Everything beyond that point depends on everything else we bring to the table.

Of course, I had read Carnegie and Cialdini, two giants in the field of influence and persuasion, as well as “Fearless Change” and The Tipping Point yet my track record in leading technical change remained checkered and uneven. After a particularly disappointing change-effort, I conducted a personal retrospective and determined that, if I was to be consistently successful as an architect and agent for transformational change, deeper study was necessary. I turned to the definitive work, “Diffusion of Innovations” by Everett Rogers and went deep into that rabbit hole.

Rogers’ book is a large and dense textbook; a comprehensive academic study of how ideas and innovations spread in social networks. After two cover-to-cover readthroughs my copy is dogeared and heavily highlighted/annotated. I dug deeper into a number of his citations. I can say the content is excellent however it was not written for me but for current and future students of the theory. What follows is my attempt to distill everything I have learned into an approachable summary for software architects and technical leaders. Although it is far from comprehensive, my goal for this post is to make the process of innovation diffusion and leading change more understandable and actionable. Whether you are architect, a leader, an innovator, or just someone wanting to move up the value chain and be more effective day-to-day, let us explore this valuable topic together.

“Only 15% of one’s financial success is due to one’s technical knowledge and the other 85% is due to human engineering and the ability to lead people

-The Carnegie Institute

How Ideas Spread

In the spirit of Everett Rogers, I will continue the tradition of referring to any kind of change we would like to see take place as an “Innovation;” an idea, practice, tool, object, or technology that has some degree of benefit for potential adopters. Successful innovation has always been a mixed bag. Innovators in all fields and walks of life have struggled with getting good ideas adopted. This has led to close to a century of focused research and several thousand publications and papers on the topic. Despite the diversity of innovations and their contexts throughout history, organizations, and society; their similarities are strikingly consistent. Change is not a technical process, but a social process. Understanding the process, the variables, and becoming more skilled in dealing with people and navigating politics is unavoidable.

Innovations, by definition, are always perceived as new to the masses (even if they are not objectively new). Of course, introducing something new requires invoking some kind of change in people (their process, behavior, beliefs, habits, etc.). Different groups adapt to change at different paces. Despite the promise of an innovation, most respondents will harbor some amount healthy skepticism about whether an innovation is an improvement on what it will replace. Innovators are generally poorly positioned to win-over skeptics. In a social sense, they are often viewed as deviants from the mainstream norms and conventions of the team, organization, or other community. The very cognitive diversity that makes us skew innovative is our downfall.

“The most innovative member of a system is very often perceived as deviant from the social system and is afforded a status of low credibility by the average members of the system. This individual’s role in diffusion (especially in persuading others to adopt the innovation) is therefore very limited.”

-Everett Rogers - Diffusion of Innovations, Fifth Edition

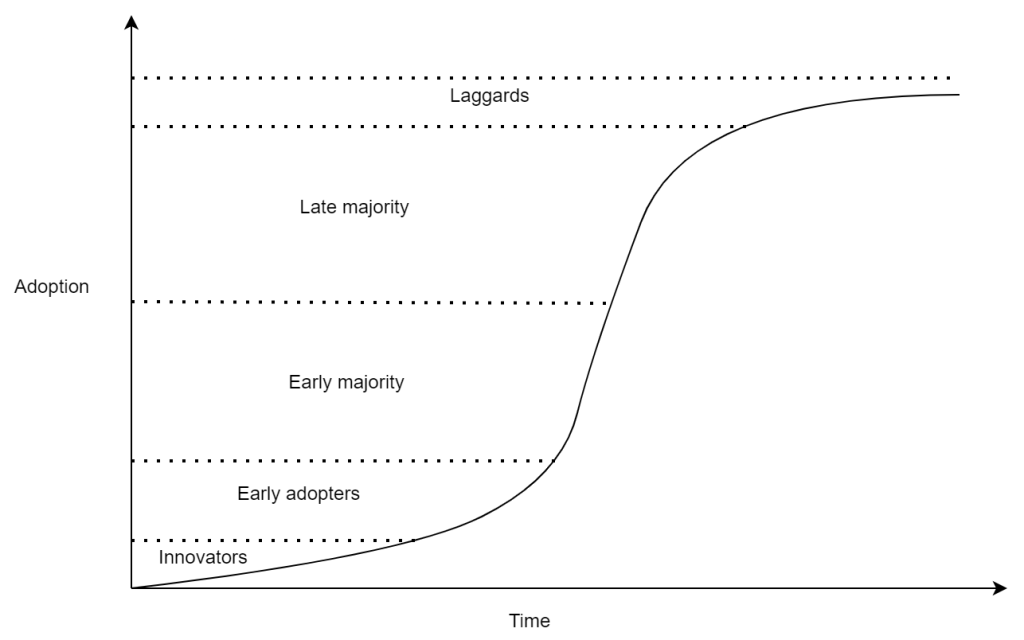

The sphere of influence of a typical innovator is relatively small. An innovation, in the hands of a small number of innovators alone, will not take root. The innovation must be increasingly adopted. In practice, successful innovations spread from the innovator to a small number of early adopters. If the early adopters are sufficiently well-regarded and well connected; the innovation will continue to spread to a larger group, the early majority. It is typically at this point that the innovation will reach a critical mass and diffusion/adoption will accelerate. As the idea spreads and repeated confirmations of success/benefit are increasingly visible, the more skeptical late majority will begin to adopt and finally the most skeptical–the laggards–will adopt the innovation. The innovation diffusion process (when successful) consistently follows an s-shaped curve over time (as illustrated below).

Diffusion and adoption are initially slow but begin to pick up as the innovation spreads to early adopters accelerating rapidly once an early majority begins to form. Achieving that critical mass of 10-20% adoption is key. As you can see from the graph, this is where the change imitative becomes self-sufficient, spreading and accelerating on its own.

Perhaps the best illustration of this is the “Dancing Guy” video and the TED talk that analyses it. From one outsider dancing alone, to a first follower, to a critical mass, to a dance party.

The “S curve” is a generalization of cumulative successful diffusion of an innovation. There are no guarantees that an innovation will go from early adopters to early majority in any given amount of time (or even at all!). In most organizations, there is often a clock on reaching critical mass. Funding can run out; initiatives can be abandoned. There is a particular set of skills and principles necessary to navigate that early space and minimize the time necessary for the innovation to take off.

From Innovator to Change Agent

Assuming you have an innovation–a technical change or improvement–that you hope will diffuse; relying on early adopters to discover and adopt your innovation by chance alone is not a recipe for success. You need to become a change agent. Becoming a change-agent requires navigating a number of hurdles. It really boils down to three things:

- The innovation and both its positive and negative attributes

- Your ability to identify key individuals in the organization (Specifically Opinion Leaders and Champions)

- Your relationships and your ability to influence those key individuals

Take any of these three away and your odds of success drop precipitously. Innovations consistently follow a common development process:

- Recognizing a problem or need

- Basic and applied research

- Formalization

- Packaging

- Diffusion/Adoption

- Consequences

In essence, given some problem, through some amount of research, the innovator develops and formalizes a solution which is then packaged in a way that it can be adopted. At this point, the diffusion process may begin and ultimately the innovation may be rejected, adopted, reinvented, or adopted then later discontinued. Steps one and two may take place out of order. It’s not uncommon for a solution to uncover a previously unrecognized problem or need (although it is equally common to see a solution invent a “need” by brute force rather than uncover one through serendipity–be cautious).

Hurdle #1 Perception of a Need

As innovators, we tend to have a pro-innovation bias. We are often techno-optimists, and our diverse knowledge and perspectives give visibility to many potential innovations. The key to success (and building credibility over time) lies in the ability to connect a potential innovation to a genuine need within an organization. Change and innovation purely for change’s sake is rarely a path to success and adoption. There must be a broad perception of value across both those individuals who have authority and influence to drive change and those who adopt it. The operative word here being perception. If we see value that others don’t, we won’t be successful; shaping perceptions is key.

Organizationally speaking, change equates to risk. Driving change requires communicating that the risk of inaction outweighs the risk of inaction. Human motivation generally falls into two distinct categories:

- Toward Pleasure (the change will make something measurably better)

- Away From Pain (the change will eliminate a major pain point)

The latter, away from pain, is universally a much stronger motivation.

Let me give you an example admittedly not related to innovation but one that illustrates how these two forces (towards pleasure/away from pain) prompt very different decision processes and how risk of action vs. risk of inaction play in: imagine it is a warm, sunny day and I am sitting happily in the hammock on my patio reading a book. I’m quite content exactly where I am, but then I hear the approaching jingle of the ice cream truck. Admittedly a Choco Taco would make my pleasant afternoon even better but obtaining one requires:

- Leaving the comfort of my hammock where I have already done the work of settling in and finding the “sweet spot.”

- Finding my wallet

- Leaving my house

- Flagging down the truck

- Purchasing my ice cream

- Returning to my house

- Re-situating myself in the hammock

I must consider the fact that:

- I am already comfortable and happy

- I might not find my wallet

- I might not have cash

- I might not get outside in time

In short, the anticipated pleasure is hypothetical until I actually have my Choco Taco in hand (which is far from a sure thing). I’m going to spend more time considering my options and may decide that taking action is not worth it.

Contrast this with another scenario. I’m in the kitchen making my signature risotto. My priority and perceived need is constantly stirring and adding liquid to the rice to achieve the perfect creamy/starchy texture. I won’t step away from this task for the ice cream truck or anything else… then I placed my hand on the hot stove. The pain is immediate and undeniable. I will instantly recoil away from the surface and, depending on how bad the pain continues to be, take further action to soak my hand in cold water and do anything else necessary to prevent the burn from becoming worse. The pain is my top priority and strong enough for me to abandon my risotto. The risk of inaction clearly outweighs the risk of action; there is no question that change is necessary. In the previous scenario, the decision process is not nearly so cut-and-dried.

Returning to our topic of innovations, we can see the importance that perception of a need and type of benefit confer to the decision/adoption process. Preventative innovations, speculative innovations, technological and process improvements that bring gradual benefit over time can be a tough sell, particularly in the absence of a perceived need (I didn’t even know I wanted a Choco Taco a minute ago). Regrettably, sometimes an innovation cannot be successfully adopted until the pain of the need is first felt. We, of course, know that “an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure” so we, as change agents, must become adept at communicating the need. If, some time before the ice cream truck appeared, my mind had somehow become focused on the idea that this sunny day would be even better with a Choco Taco in hand, I would be more apt to take action when I heard the ice cream truck approaching. This suggests that some part of our effort must be spent building awareness of the problem before presenting the solution; what Robert Cialdini calls “Pre-Suasion”. The difficulty of this hurdle is compounded by the fact that different individuals will perceive and respond to different aspects of both the problem and solution. There are multiple “stories” about the problem/need that must be told for each audience.

Hurdle #2 Finding a Solution

In today’s era of technological marvels and miracles, it seems there is a solution for everything. At first glance, this seems easy, but a potential solution must be evaluated holistically. It must not only meet the needs/solve the problems of the organization, but it must also be an innovation within reach of those who must adopt it. As a practicing software architect, I often have what I believe is the optimal solution for a given project, only to realize that this first iteration of the innovation will either involve a much larger scope of change (more risk) or compromising the innovation for compatibility (more risk). The Tailor-Made Architecture Model is an approach to optimize how we design, evaluate, and communicate architecture with this reality in mind. This aspect of the innovation process is often much more challenging than it may first appear, and a would-be innovator must be skilled in navigating this process.

Hurdle #3 Packaging for Adoption

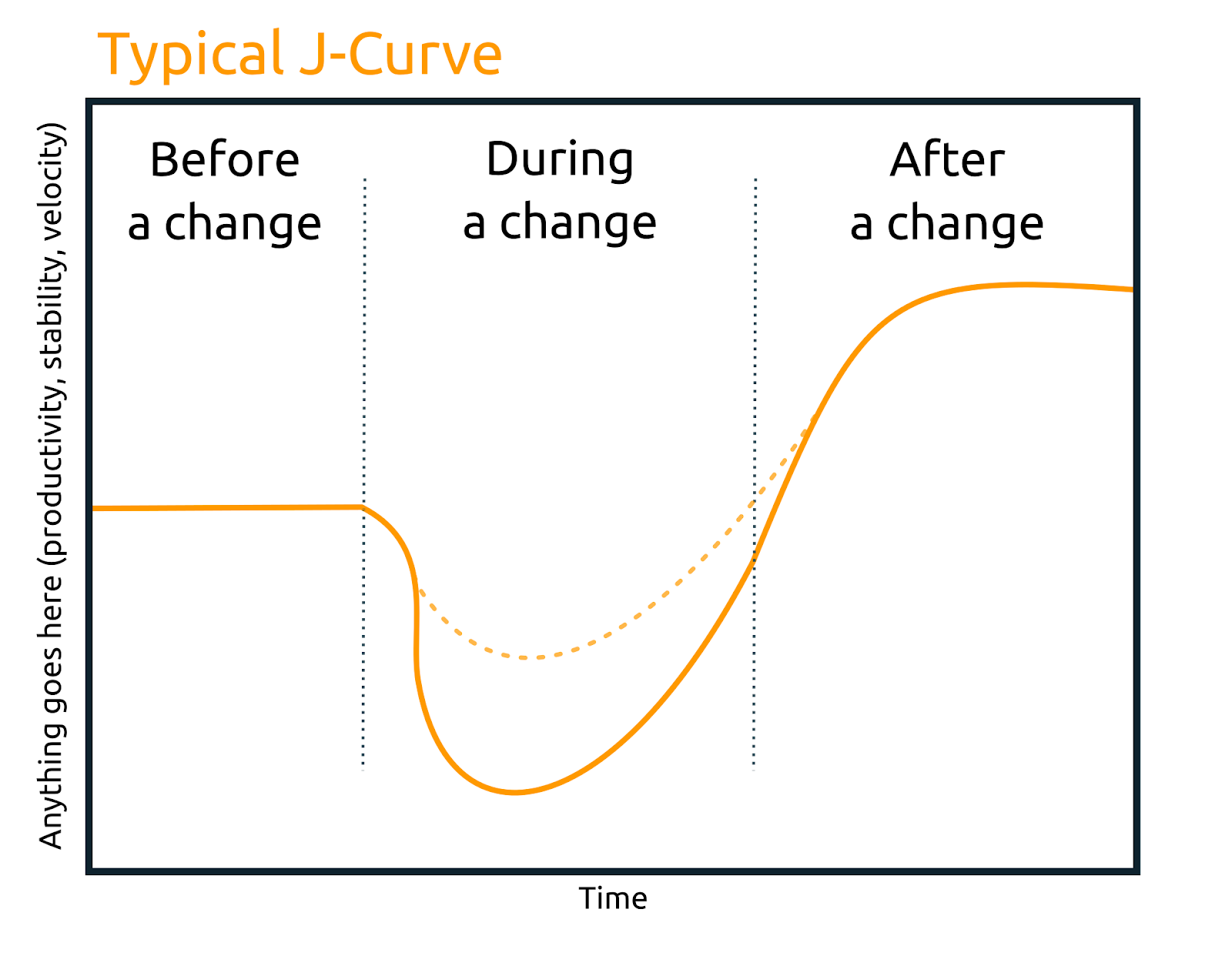

Even once the innovation is well-defined, the potential benefits understood, and the formalized solution optimized for the organization; more work is necessary. Typically, some amount of effort is necessary to “package” the innovation into a form that is ready to be adopted. Often innovators can be overly excited, with a strong desire to unleash the innovation on the world, but it is important to proceed carefully here. Virtually any change invites some disruption, exemplified by the “J curve.”

There is often an expectation and implicit assumption (by both innovators and potential adopters) that the innovation will trace a steady improvement over time but, almost universally, the innovation brings a striking initial disruption that must be overcome. Many promising innovations are abandoned during the j-curve dip. Proper packaging of an innovation is a crucial step. The less potential adopters have to learn and the fewer ingrained behaviors/habits they need to change, the better the odds of success for the innovation.

Packaging is the process of removing as much initial adoption friction as possible. Packaging may involve building a POC, reference implementation, or tooling. It may involve training or coaching/mentoring. There is no one-size-fits-all approach.

Hurdle #4 Reaching Critical Mass

Even if properly packaged, the innovation must find a critical mass of early adopters. You will not succeed if you try to “boil the ocean” and endeavor to convince everyone at once. The vast body of work on diffusion theory consistently shows the universal spread of ideas and subsequent acceleration from the small group that is more open to new ideas to the larger groups that tend to be more skeptical. Regardless of the change agent’s efforts, the early majority’s adoption decision and investment will depend on seeing the success of the early adopters (and so on, up the curve). Focusing communication and persuasion efforts on the right early adopters is a better use of time and energy. Think of early adopters are the local gatekeepers of new ideas and technologies and they bridge the gap between innovators and the larger community within the organization. Early adopters are generally considered a bellwether for the success of the innovation within the organization. Not all early adopters are created equal; you’re specifically looking for “Opinion Leaders” who are respected by their peers and are considered more integrated within their social systems than Innovators yet are not too traditional/resistant to change.

Some time ago, I wrote about the my experiences with the Dvorak keyboard, an optimized and human-centric redesign of the keyboard layout that improves speed, efficiency, and reduces RSI. It solves a problem (yet the perception of the need is not widespread), it has been carefully designed and formalized, and has even been packaged for adoption (every major OS ships with a Dvorak layout option, alternatively designed/labeled keyboards are available, hardwired keyboards are available) yet the innovation has been lingering in the “early adopter” phase of diffusion for close to a century. Every innovation that fails to reach critical mass will either die on the vine or languish in obscurity.

Hurdle #5 Managing the Diffusion Process

Once the diffusion process “takes off” there is this assumption that success is inevitable however, without careful planning and management of this process, the innovation may still fall flat. First, we must accept the very real possibility that the promised benefits don’t materialize. In this case the innovation is typically discontinued or abandoned. Our only real option in this case is to perform a postmortem on the change effort and learn what we can to improve our mental models and process.

We must also be aware of the phenomenon of reinvention. In tackling hurdle #2, we do our best to fit the innovation to the organization but, in most cases, the organization will modify the innovation during adoption. This happens for a number of reasons:

- Innovations that are hard to understand are more likely to be re-invented

- Reinvention can occur owing to an adopter’s lack of detailed knowledge about the innovation.

- An innovation that is a general concept or a tool with many possible applications is more likely to be reinvented - see the web

- When an innovation is implemented to solve a wide range of users’ problems, reinvention is more likely to occur.

- Reinvention may occur because a change-agent influences its clients to modify or adapt an innovation

- Reinvention occurs when an innovation must be adapted to the structure of the organization

- Reinvention may be more frequent later in the diffusion process as later adopters profit from the experience gained by earlier adopters.

Although we lose some control of the direction, often innovation reinvention is a positive thing. Reinvention correlates positively with adoption and sustainability, however reinvention can also transform diffusion into dilution. Arguably the widespread diffusion of concepts such as agile and DevOps have led to such a high degree of reinvention that they no longer address the original problems/needs that led to their development and what they have become have increasingly little value in most organizations. A strong, unifying focus on the problem and the why is key to preventing dilution during diffusion.

Understanding the Attributes of an Innovation

Clearing any or all the hurdles identified is not a guarantee of success, nor is reaching critical mass. Even successful widespread adoption is not the finish line. There are no guarantees in the diffusion of innovation, but we can optimize the process to best position ourselves for success. This begins with five key attributes of an innovation that must be explored, understood, and optimized. They are:

| Attribute | Definition |

|---|---|

| Relative Advantage | The degree to which an innovation is perceived as better than the idea it supersedes. |

| Compatibility | The degree to which an innovation is perceived as being consistent with the existing values, past experience, and needs of potential adopters. |

| Complexity | The extent of the difficulty or friction adopters experience in attempting to adopt an innovation |

| Trialability | The degree to which an innovation may be experimented with on a limited basis. |

| Observability | The degree to which the results of an innovation are visible to others. |

Each of these attributes correlates either positively or negatively to the rate or likelihood of adoption and are common to virtually every innovation. Looking at any innovation through the lens of these variables can prove illuminating. Sometimes the innovation is not perceived as advantageous, sometimes the advantages are clear but people are too set in their ways or can’t make time for change. Sometimes the change is just too complex. Let’s look at these in the context of a common example:

Some time ago, industry analyst Gartner made a prediction that by the end of 2019, “90% of organizations who try to adopt the microservices architecture will fail; they will find the paradigm too disruptive.” I believe this is a perfect example of the challenges with the diffusion of innovation. There is this idea that the perceived superiority of the idea will win out and everyone will “jump right on board” however, in reality, adoption of microservices requires many radical changes.

Gartner is not explicit about what is meant by “they will find the paradigm too disruptive” but if we look at this through the lens of Rogers Innovation Diffusion Theory, we can explore the attributes of the innovation:

Relative Advantage

Executed well, microservices promise a great deal of relative advantage in terms of system quality attributes such as agility, scalability, elasticity, fault-tolerance, etc. Additionally, there is much social prestige to be had (often, in fact, this becomes a significant driver). Given industry giants such as Amazon, Netflix, Google, and others adopt microservices; the perception is microservices is a “real” architecture and confers significant bragging rights.

When talking about objective advantage, perception is key; feelings are facts. The degree of objective advantage doesn’t matter so much. It’s all about perception - does the individual perceive the innovation as advantageous? In the case of microservices, the perception of relative advantage in the mind of a would-be innovator is so strong that many pursue this approach as folly. In fact, quite frequently, microservices are a solution to a problem an organization simply doesn’t have (although there are often other factors). There will be members of the organization who are skeptical of this type of change as they see the risks associated with the change and aren’t quite so swayed by the hype, the “true believers” of the perceived advantage often drown out these voices.

Executing this architecture well requires major organization-wide changes, some of which are incredibly disruptive. If the “why”–the relative advantage–is not widely shared in an organization, it can be hard to overcome innovation compatibility and complexity.

Innovation Compatibility

Microservices is a domain-partitioned architecture. In other words, microservice boundaries are defined by business domain and business context boundaries. To put this architecture in practice we must accept what Melvin Conway first postulated in 1967–and has been since demonstrated again and again in studies–that “organizations designing systems tend to produce designs that mirror their own communication structures.” In other words, the technical architecture of a system reflects the social boundaries and interactions within the organization that created it. For most organizations, entire divisions or the entire company must be restructured. This begins with an extremely expensive and lengthy analysis process and ends with major organizational changes. Well established communication lines are massively changed, areas of focus and expertise radically shift, teams might be broken apart and reformed. This is, by definition, a very incompatible change. If the relative advantage is not black-and-white clear to all involved, such an innovation will be abandoned or reinvented (typically the latter).

For developers and teams, several more incompatible changes follow. Decades of convention and “best practices” that have been drilled into their heads are suddenly invalidated. To achieve the goals of independent release cycles and “extreme decoupling,” Microservices play by a very different (and seemingly foreign) set of rules.

Would-be innovators who charge head-first into a microservice strategy rarely consider the innovation compatibility attributes.

Old ideas are the main mental tools that individuals utilize to assess new ideas and give them meaning. Individuals cannot deal with an innovation except on the basis of the familiar.

For the majority of organizations and developers adopting this strategy for the first time, there is very little that is familiar in this innovation. In addition to low compatibility, this innovation is extraordinarily complex.

Innovation Complexity

Microservices are incredibly difficult to implement well. Distributed systems require vastly different mental models and disciplines that do not typically come naturally. Long-held best practices such as “don’t repeat yourself” (DRY) are now anathema to good software. Teams must work independently which often requires interface-first development; it is not easy to begin thinking in terms of abstractions. Teams must also develop new skills surrounding automation and DevOps.

Andrei Taranchenko wrote extensively about the amount of churn, change, and friction microservices can introduce in his blog post “Death by 1000 microservices”.

This compatibility aspect is a significant hurdle to Innovation Diffusion. This also begins to speak to the phenomenon of Innovation Reinvention.

Innovation Reinvention

This is the degree to which an innovation is changed or modified by a user in the process of adoption and implementation. This is another aspect of innovation diffusion that is rarely considered. Once an innovation begins to diffuse, it is rarely within the control of the initial innovator.

Two forces are at play here. First, many adopters want to actively participate in customizing an innovation to fit their unique situation. In other words, they want to put their name on it in a sense. Second, incompatible innovations are often reconciled with the familiar. Remember:

Old ideas are the main mental tools that individuals utilize to assess new ideas and give them meaning. Individuals cannot deal with an innovation except on the basis of the familiar.

The fine-grained and extremely decoupled nature of microservices is rarely compatible with established values and norms of most developers. The more coarse-grained and greatly simplified “mini-services” or “macro-services” that emerge in the “90%” Gartner talks about is a reinvention that emerges in response to the compatibility and complexity aspects of this change. While some innovations provide ample room for reinvention, microservices offer comparatively few dimensions for reinvention that don’t negatively impact other teams and the rest of the system. In short, microservices architecture requires teams optimizing for organization-level goals and optimizing for team-level goals will lead to a “tragedy of the commons” and a failed/discontinued implementation.

To manage innovation reinvention, the innovator/change-agent must think about how this innovation will spread through the organization. How can they scale themselves; how can they identify influential champions and experts who can help steer the early majority during the innovation diffusion process?

Innovation Observability

At a high level, the degree to which the results of an innovation are visible to others. The easier it is to see the results, the more likely they will adopt. When a team or organization sees someone else experiencing success with an innovation, the more likely they will adopt. Observability has another important component here in managing reinvention and avoiding micromanaging the innovation. It is much easier to establish “systems” than to attempt to micromanage innovation diffusion. Observability is key in the setting of feedback loops and improving the odds of a successful innovation.

Innovation Trialability

Microservices are often initially treated as all-or-nothing affairs where the innovation is framed as radical, overnight change. Innovations that can be trialed will be adopted more quickly. Rogers gives the example of farmers adopting new hybrid corn and trying a small amount on limited acreage and he goes on to say:

The trialability of an innovation, as perceived by the members of a social system, is positively related to its rate of adoption.

This reduces the perceived risk of the change and allows for the innovation to progressively become more compatible to the organization and teams.

Notably the innovator/change-agent must consider these aspects up-front and navigate this space carefully. A more constrained “trial” of the architecture, perhaps splitting out one or two microservices from a monolith would provide an opportunity for a more limited and managed trial. Also trialing a more coarse-grained, “mini-service” might provide a path with more relative compatibly and allow architecture and development to iterate on the optimal architecture from a complexity/compatibility standpoint while serving as an observable success for the early majority to observe, follow, and adopt.

Optimizing Innovation Attributes

If our goal is to be successful as innovators and influential as change-agents, we must think about how we can optimize these five attributes central to the success or failure of the innovation. This must take place both as part of the solutioning process and the design process. This is true regardless of how the diffusion decision will be made (i.e. optional, collective, or authority mandate).

My friend and fellow software architect, Daniel Tippie, will frequently point out that there are five elements necessary to effect change in an organization. They are:

- Authority

- Accountability

- Responsibility

- Know-How

- Will

Rarely will any single individual possess all five. On the spectrum of roles in an organization, from business-focused to technically-focused, those with authority and responsibility will typically occupy the business-side of the spectrum. Know-how and will must exist broadly on the technical side. That leaves us, the innovators and would-be change-agents. We may have know-how and will for change, but that is insufficient; those actually adopting/implementing the innovation will also require know-how and will. Success requires optimizing the innovation attributes from the perspective of both sides of the organization and the respective roles.

Optimizing Relative Advantage

Obviously the higher the perceived relative advantage of the innovation, the higher the likelihood of adoption. The degree of relative advantage may be measured in economic terms, but social prestige factors, convenience, and satisfaction are also important factors. Relative advantage, however, is always in the eye of the beholder. Savvy and adroit change agents will look at relative advantage from multiple angles. When presenting the innovation to potential early adopters and champions, you must be able to succinctly communicate both what the innovation is and why they should care. For technical innovations, I usually summarize this as:

- What is the thing?

- What does it do?

- Why should I care?

The precise framing of this message will vary depending on the audience.

Authority-Driven Decisions

This type of decision typically leads to the fastest rate of diffusion as, generally, far fewer individuals are involved in the actual adoption decision. In this case, the relative advantage of the innovation must be framed in terms the authority (typically a business person) understands and resonates with.

A common error many would-be change-agents make is communicating the value of the innovation in terms of benefit to themselves. e.g. Exclaiming to the business “Hey, if we bought this expensive piece of software, my job would be so much easier!” That may be true, but the business doesn’t necessarily care about making your job easier. Figure out what they do care about and frame the benefits from that perspective. Maybe the consequence of your job getting easier is a higher speed-to-market, or lower defect escape rate, or whatever OKR/Metric they care about. The chances are your job being easier will result in one or more business benefits. You must find these and communicate them.

Authority buy-in and mandate only satisfies three of the five necessary change elements from the Tippie model; know-how and will are still necessary, meaning packaging/training (know-how) and will (relative advantage) must be broadly communicated. For this reason, further relative advantage optimizations must be made for the broader audience and some care given to communication channels.

Collective Decisions

Collective decisions are made by consensus among members of a team or organization. Generally, these types of decisions take longer to reach a point of consensus but the resulting decision is often more sustainable. These types of decisions usually begin with a common awareness of the problem or need and the opportunity for members of the organization to exercise some agency and autonomy in their direction elicits a sense of “ownership” in the final decision which contributes greatly to the element of will.

Generally, an innovator-turned-change-agent will have some idea of a solution in advance, but getting broad-scale acceptance of the innovation can be like herding cats. Optimizing relative advantage in this scenario often begins with a focus on the problem. Before simply pitching your innovation, create an environment where members of the community can contribute their perspectives on the problem/need; let them communicate their pain points. The optimum communication of relative advantage is focused on what matters most to the adopter. Therefore, pay close attention to the who and what of the pain points (particularly from influential members of the group) and use this information to effectively frame relative advantage.

Individual/Optional Decisions

This type of innovation decision involves the most people and is often the slowest to diffuse. This type of innovation decision involves the broadest audience so it can be useful to consider how to segment the various audiences based on common pain-points. Like the collective decision, this positions you as the change agent to speak meaningfully and impactfully about the relative advantage of the innovation. Operating effectively, however, involves the change-agent scaling themselves. It can be useful to identify influential members within each community/segment, tailor the message to them, and empower them to spread the message with their peers.

Given the broad need for know-how and will, even in authority and collective decisions, this skill and practice should be kept in mind and care and thought put into communication channels.

Optimizing Compatibility

A strong belief in the benefits of an innovation often leads would-be innovators to assume that the practices it seeks to replace are so inferior they can be completely dismissed yet history repeatedly shows the folly in this thinking. Adopters can only deal with an innovation within the context and basis of what is already familiar. You must ask yourself how compatible your innovation is with the existing ways of working and existing mental models.

The truly revolutionary ideas (relatively speaking) simply cannot be introduced all at once. As Nikola Tesla’s character in the 2006 film, “The Prestige” says,

“The world only tolerates one change at a time.” -The Prestige

Personally speaking, one of the hardest realities I have had to accept in my career is meaningful change often must take place in stages. On a case-by-case basis, the innovation must be evaluated to determine if the big innovation can be broken down into smaller, more compatible changes that pave the way toward the final innovation.

In 2017 I wrote a conference talk entitled “Persuasion Patterns” which included a case study of a Continuous Delivery transformation within an organization. The full scope and scale of the innovation was far too much to succeed. Ultimately the innovation was reduced into a large number of bite-sized innovations that could incrementally be adopted. Over time, the broader ideas became more familiar, the innovation more compatible, and the innovation ultimately succeeded.

Every innovation must be ruthlessly examined to identify potential areas of flex or deferral. Perfection is the enemy of progress.

Optimizing Complexity

New ideas that are simpler to understand are adopted more rapidly than innovations that require the adopter to develop new skills and understandings. Similar to how we must approach compatibility, ruthless examination must take place to identify where ideas can be simplified in the short term. We must look for every opportunity to reduce adoption complexity.

I find that taking time to create learning guilds, book clubs, or regular lunch-and-learn sessions are an ideal forum to gradually introduce ideas into the organization well-before pitching them as innovations. This creates a foundation of fertile soil for future learning on a topic to take root and blossom.

It is also important to have “skin in the game.” Taking the time to build POCs, tooling, reference implementations can aid greatly. Automation is another avenue to reduce friction points. Finally, consider a training strategy. You may possess the skill of building effective and engaging training but also consider how you can scale yourself.

Optimizing Trialability

To many would-be adopters and champions, change almost universally equates to risk. An innovation that can be evaluated on a trial basis is one with significantly lower risk. The value of presenting a trial should not be underestimated. As a personal example, I have always struggled with my weight to some extent and I am currently down 70lbs (~32kg) from my highest weight. At one point on that downward journey, my doctor recommended increasing caloric and fat intake which was definitely not compatible with my decade or so of diets. Then she said “We’ll do it for six weeks. There’s no amount of damage you can do in six weeks that you can’t undo in that amount of time or less.” It was only then that I agreed. It was the right approach (and I’ve maintained my goal weight for a number of years since).

I once used this same line on a manager when proposing a significant change to our SDLC (“we can undo anything in six weeks”). Resistance was overcome and the change was successful.

Think carefully about the opportunities to trial an innovation. First the limited perceived scope of the risk will win over some who are skeptical, but also consider the trial as part of building your growing body of early adopters. Relatively earlier adopters of an innovation perceive trialability as more important than do later adopters. (since we can see others success later in the adoption curve). Peers are, in essence, a vicarious trial.

Optimizing Observability

“You can’t improve what you don’t measure.” -Peter Drucker

Each adopter group has a different threshold for uncertainty. Early adopters are comfortable with more uncertainty, the late majority is comfortable with significantly less. As the innovation makes its way through the S curve, uncertainty about the innovation should be steadily decreasing. Increasingly, potential adopters should be seeing that:

- The innovation is successful

- The problem is tractable

- The benefits are materializing

- This is better than the status quo

The challenge for the change agent is making this data visible. In the past I have attempted to find metrics germane to various groups I wish to influence in the organization. On the business side I have looked at OKRs, financials, and other relevant metrics. For technical groups I have measured a downward trend in out-of-hours support calls, escaped defects, or other pain points.

The key is to figure out what you can measure and show to reduce uncertainty and communicate this.

Relationships and Influence

By now it should be clear that skill in communication, building relationships, and persuasion are critical. How we manage communication, and the extent of our efforts have significant impact on the rate at which the innovation is adopted.

Variables in determining the adoption rate of innovations

To maximize your efforts as a change agent and optimize influence and communication, I recommend reading Influence, The Psychology of Persuasion and Pre-Suasion by Robert Cialdini, along with the classic How to Win Friends and Influence People by Dale Carnegie. These are three valuable books with much to teach. Perhaps I will write a future post distilling their teachings into this topic.

In summary, well before trying to influence anyone, begin to build positive and productive relationships as widely as possible. Be the first to offer support in any relationship and always give more than you ask for. Build good friendships and positive working relationships. Learn to communicate effectively and persuasively.

Wherever possible when communicating with a group or committee, let members of this committee propose their own solutions. Where competing (but inferior) solutions are proposed, ask questions rather than contradict. Allow shortcomings of competing innovations to be discovered by–rather than dictated to–members. Preserve collective ownership of the idea rather than seeking credit.

Conclusion

This post has become significantly larger than I anticipated. There is so much more I want to write but that must wait for a follow-up piece. The takeaway, perhaps, is simply that becoming a change-agent who makes innovation happen is a long game. There are no shortcuts, there are no tricks. It requires a unique set of skills, foresight, and planning to become effective. While we many never master these skills, even bare proficiency will make us more effective in whatever role/title we hold now and in the future. Being able to lead technical change will also result in a much more satisfying career and life.

As a practicing software architect, I have long since learned that, without these skills, I cannot be effective. I find these skills and practice to be of equal importance (if not, even more so) to my hard “architect” skills. The more time I spend in this industry, the more I find this is true in all roles and cases, regardless of title or seniority.

In short, this is a topic I am very passionate about. If you read this far, please know I believe we are kindred spirits and if you ever need advice or assistance, you’re free to call on me anytime.